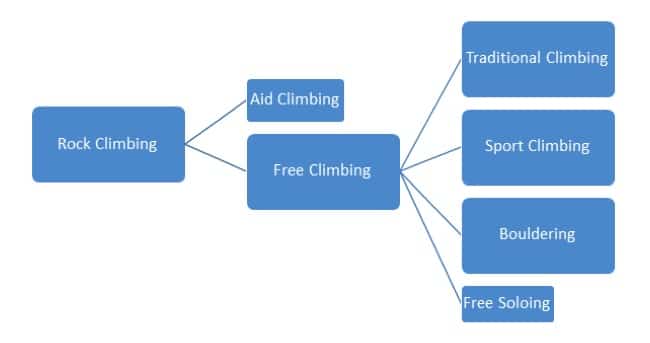

Types of Rock Climbing. Learn the main characteristics and specific techniques of the different ways of climbing.

Rock climbing is a sport with a wide range of sub-disciplines. This guide offers an overview of the different climbing styles, characteristics and techniques.

1. SPORT / LEAD CLIMBING

Sport climbing is a form of rock climbing that relies on permanent anchors fixed to the rock for protection, in which a rope that is attached to the climber is clipped into the anchors to arrest a fall. This is in contrast to traditional climbing where climbers must place removable protection as they climb. Sport climbing usually involves lead climbing techniques, but free solo and deep-water solo (no protection) climbing on sport routes is also sometimes possible.

Sport climbing emphasises strength, endurance, gymnastic ability and technique.

With increased accessibility to climbing walls, and gyms, more climbers now enter the sport through indoor climbing than outdoor climbing. The transition from indoor climbing to sport climbing is not difficult because the techniques and equipment used for indoor climbing are nearly sufficient for sport climbing.

Since sport climbing paths do not need to follow climbing paths where protection can be placed they tend to follow more direct, and straight forward, paths up crags than traditional climbing paths which can be winding and devious by comparison. This, in addition to the need to place gear, tends to result in different styles of climbing between sport and traditional.

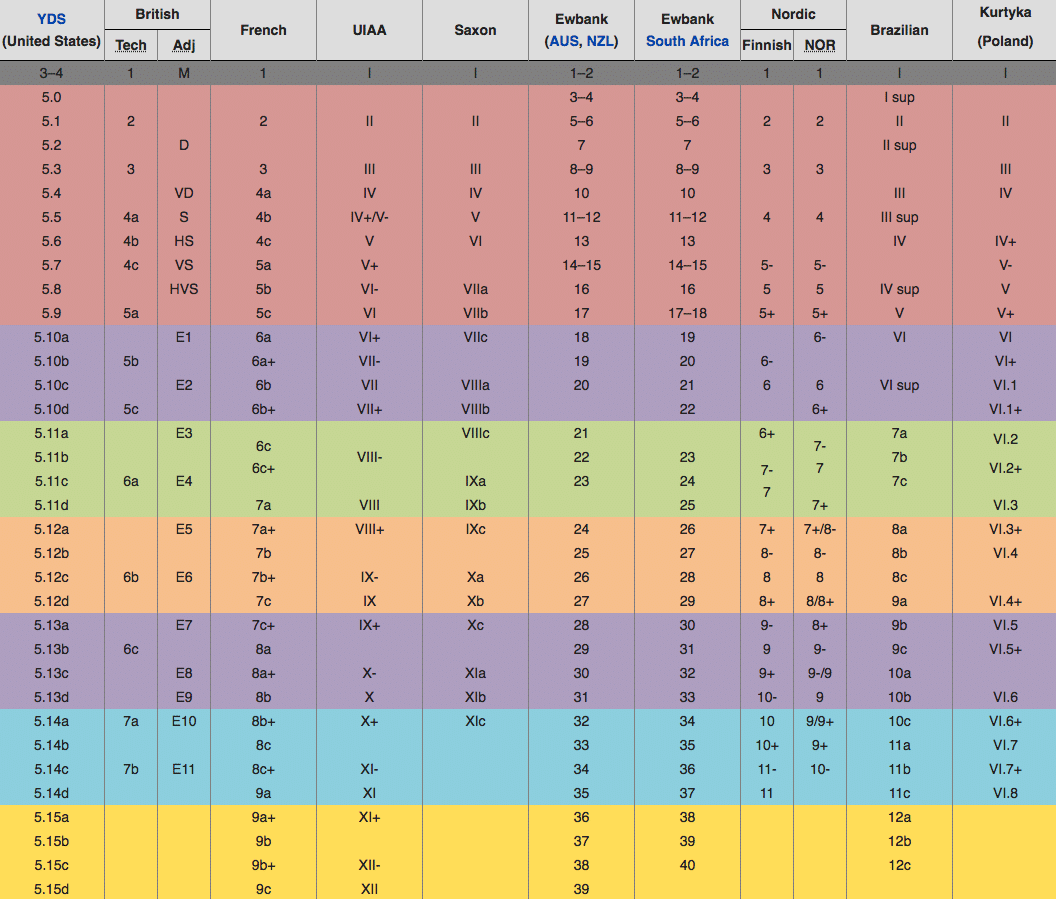

1.2. FREE CLIMBING GRADES

The following chart compares some of the free climbing grading systems in use around the world. As mentioned above, grading is a subjective task and no two grading systems have an exact one-to-one correspondence. Sport climbs are assigned subjective ratings to indicate difficulty. The type of rating depends on the geographic location of the route, since different countries and climbing communities use different rating systems. In Spain we use the French grading for sport climbing difficulty with little variations.

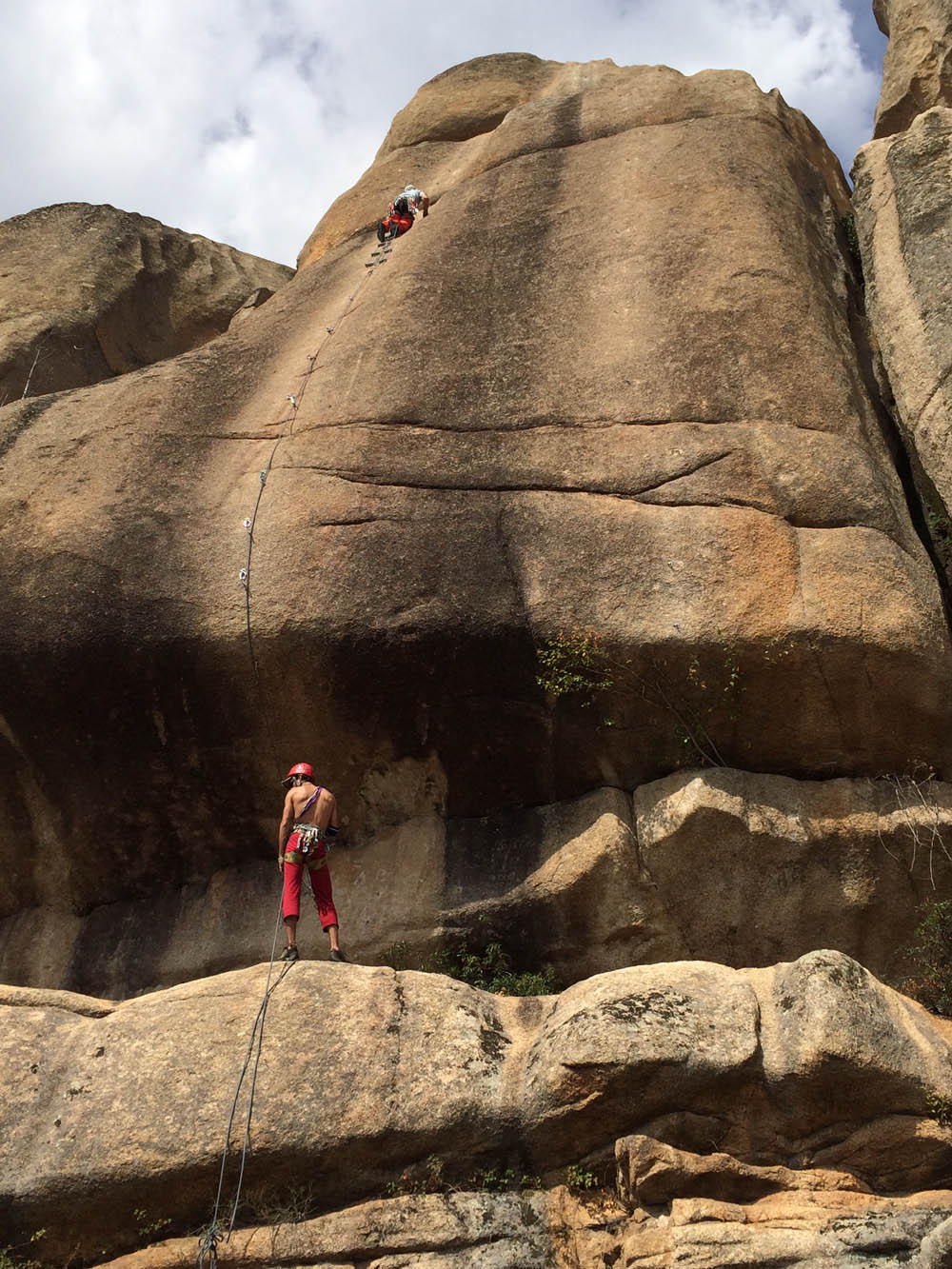

2. TRAD CLIMBING

Traditional or trad climbing, is a style of rock climbing in which a climber or group of climbers place all gear required to protect against falls, and remove it when a pitch is complete. Traditional bolted face climbing means the bolts were placed on lead and/or with hand drills. The bolts tend to be much farther apart than sport climbs.

Characterizing climbing as traditional distinguishes it from bolted climbing—either trad bolted or sport climbing (in which all protection and anchor points are permanently installed prior to the climb — typically installed while rappelling) and “free solo climbing” (which does not use ropes or gear of any kind). However, protection bolts, pitons and pegs installed while lead climbing are also considered “traditional” as they were placed during the act of climbing from the ground-up rather than on rappel, especially in the context of granite slab climbing.

Before the advent of sport climbing in the United States in the 1980s, and perhaps somewhat earlier in parts of Europe, the usual style of unaided rock climbing was what is now referred to as traditional-either bolted face climbs or crack climbs. In trad climbing, a leader ascends a section of rock placing his or her own protective devices while climbing. Before about 1970 these devices were often limited to pitons; today they consist mainly of a combination of chocks and spring-loaded camming devices, but may less commonly include pitons which are driven with a hammer

Important features of trad climbing are a strong focus on exploration, and a strict dedication to leaving nature unblemished by avoiding use of older means of protection such as pitons, which damage the rock. This evolution in climbing ethics has been attributed to the efforts of Yvon Chouinard, Royal Robbins, and many others, who pioneered the “leave no trace” ethic in climbing

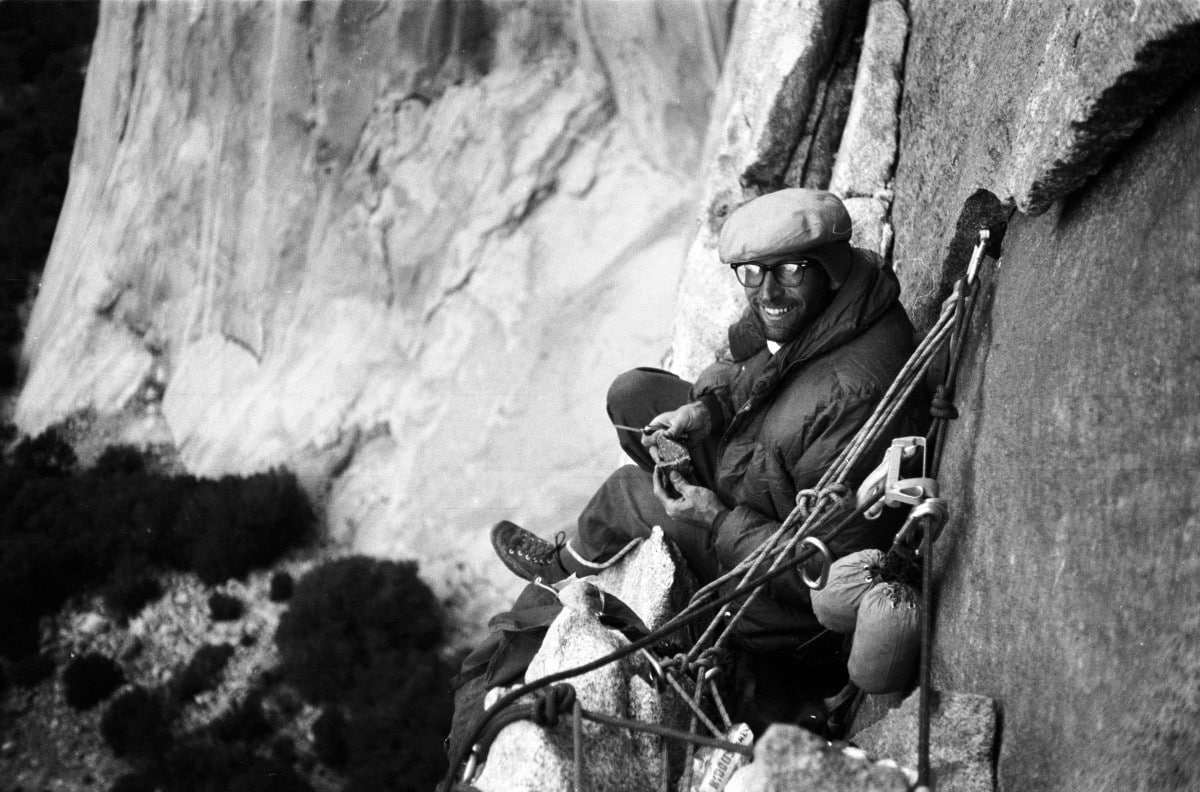

3. BIG WALL CLIMBING

Big wall climbing is a type of rock climbing where a climber ascends a long multi-pitch route, normally requiring more than a single day to complete the climb. Big wall routes require the climbing team to live on the route often using portaledges and hauling equipment.It is practiced on tall or more vertical faces with few ledges and small cracks.

In order to haul portaledges and other gear such as ropes, food, and water up a rock face, the gear is put in a bag (“haul bag” or “pig”) and pulled up to the next belay station. There are many different mechanically advantageous systems, such as counterweighting, that are utilized to make pulling up the “haul bag” easier than simply dragging it up the face.

Gear is usually spread over many haul bags (usually packed so that they weigh between 30 and 40 kilograms) in order to maximize efficiency and limit loss of equipment if a bag is lost. The hauling system usually consists of a self-locking pulley in order to capture the motion and prevent the bag from descending once hauling stops. Next, an ascender clamped to the haul rope is used to pull the haul line through the pulley.

In the early 20th century, climbers were scaling big rock faces in the Dolomites and the European Alps employing free- and aid- climbing tactics to create bold ascents. Yet, the sheer walls were waiting to be climbed by future generation with better tools and methods.

Thanks to the innovation of Emilio Comici, he was the inventor and proponent of using multi-step aid ladders, solid belays, the use of a trail/tag line, and hanging bivouacs, contributing greatly to the techniques of big wall climbing, in the late 1950s big wall climbing finally started. In Yosemite, the northwest face of Half Dome was climbed in 1957 and the southeast buttress of El Capitan in 1958. With the invention of hard iron pitons, jumars and hammocks, wall climbing exploded in the 1960s and 1970s.

Following those pioneering achievements, parties began routinely setting off prepared for days and days of uninterrupted climbing on very long, hard, steep routes. The food, water, hardware and shelter necessary for such a climb could easily weigh well into the hundreds of pounds. Hauling systems were developed for managing these large loads.

In the last few decades, techniques for big wall climbing have evolved, due to greater employment of free-climbing and advances in speed climbing. The routes that used to routinely take days can be climbed in under 24 hours. Nevertheless, many parties still do make multi-day ascents of classic “trad routes” which have recently gone mostly free and very fast. Only a small handful of elite and exceptionally well-prepared climbers are capable of feats such as free-climbing the entirety of most classic Grade VI routes, or of speed-climbing such routes in a matter of hours.

4. AID CLIMBING

Aid climbing is a style of climbing in which standing on or pulling oneself up via devices attached to fixed or placed protection is used to make upward progress.

The term contrasts with free climbing in which progress is made without using artificial aids: a free climber ascends by only holding onto and stepping on natural features of the rock, using rope and equipment merely to catch them in case of fall and provide belay.

In general, aid techniques are reserved for pitches where free climbing is difficult to impossible, and extremely steep and long routes demanding great endurance and both physical and mental stamina. While aid climbing places less emphasis on athletic fitness and raw strength than free climbing, the physical demands of hard aid climbing should not be underestimated.

Aid climbing is sometimes errantly referred to as class 6 climbing, as it relies on ascent by one’s equipment rather than merely being protected by it. It is regarded by purists as falling outside the traditional Classes 1–5 Yosemite Decimal System rankings that rely on making progress with one’s hands and feet in direct contact with the rock alone. Aid climbing has its own ranking system, using a separate scale from A0 through A5.

A0 Pulling on solid protection, often without the use of étriers.

A1 Easy aid, no risk of any piece of protection pulling out. Safe falls.

A2 Moderate aid. Short sections of tenuous placements above good protection.

A2+ May include easier A3 moves but is not hard enough to be rated as such.

A3 Hard aid. Involves many tenuous placements in a row.

A3+ May include easier A4 moves but is not hard enough to be rated as such.

A4 Runout, complex and time-consuming. Many body weight placements.

A4+ May include easier A5 moves but is not hard enough to be rated as such.

A5 Serious, hard aid with huge falls and possibly lethal results.

5. BOULDERING

Although every type of rock climbing requires a high level of technique and strength, bouldering – the most dynamic form of the sport – requires the highest level of power, and thus places considerable strain on the body.

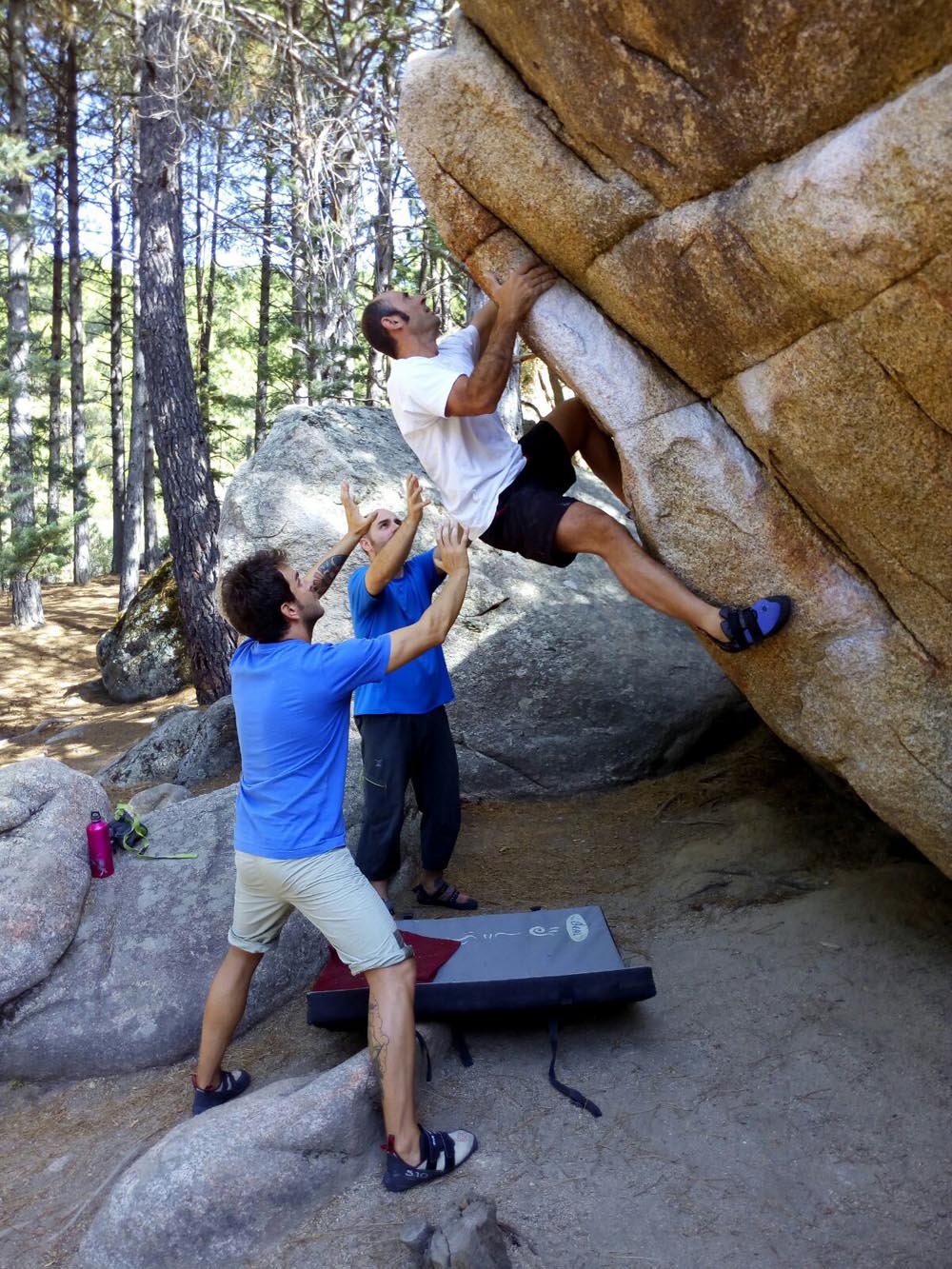

Bouldering is a form of rock climbing that is performed on small rock formations or artificial rock walls without the use of ropes or harnesses. While it can be done without any equipment, most climbers use climbing shoes to help secure footholds, chalk to keep their hands dry and provide a firmer grip, and bouldering mats to prevent injuries from falls. Unlike free solo climbing, which is also performed without ropes, bouldering problems (the sequence of moves that a climber performs to complete the climb) are usually less than 6 meters (20 ft.) tall. Traverses, which are a form of boulder problem, require the climber to climb horizontally from one end to another. Artificial climbing walls allow boulderers to train indoors in areas without natural boulders. In addition, bouldering competitions take place in both indoor and outdoor settings.

The sport originally was a method of training for roped climbs and mountaineering, so climbers could practice specific moves at a safe distance from the ground. Additionally, the sport served to build stamina and increase finger strength. Throughout the 20th century, bouldering evolved into a separate discipline.[3] Individual problems are assigned ratings based on difficulty. Although there have been various rating systems used throughout the history of bouldering, modern problems usually use either the V-scale or the Fontainebleau scale.

The characteristics of boulder problems depend largely on the type of rock being climbed. For example, granite often features long cracks and slabs while sandstone rocks are known for their steep overhangs and frequent horizontal breaks. Limestone and volcanic rock are also used for bouldering.

To prevent injuries, boulderers position crash pads near the boulder to provide a softer landing, as well as one or more spotters (people watching out for the climber to fall in convenient position) to help redirect the climber towards the pads. Upon landing, boulderers employ falling techniques similar to those used in gymnastics: spreading the impact across the entire body to avoid bone fractures, and positioning limbs to allow joints to move freely throughout the impact.

There are many prominent bouldering areas throughout the United States, including Hueco Tanks in Texas, Mount Evans in Colorado, and The Buttermilks in Bishop, California. Squamish, British Columbia is one of the most popular bouldering areas in Canada. Europe also hosts a number of bouldering sites, such as Fontainebleau in France, Albarracín in Spain and various mountains throughout Switzerland. Africa’s most prominent bouldering areas are the more established Rocklands in South Africa and Hampi in India.

In Madrid you can practice bouldering in La Pedriza, El Escorial, Zarzalejo and La Cabrera.

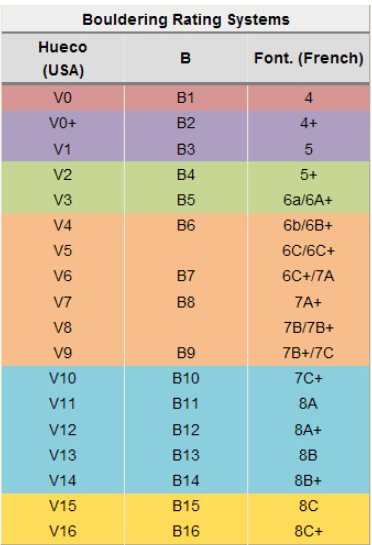

5.1. BOULDERING GRADES

These table shows the comparison rating system for bouldering according to Hueco (USA), B (British) and Fontainebleau (French). In Spain we use the french grading for bouldering difficulty.

6. HIGHBALL BOULDERING

Highball bouldering is simply climbing high, difficult, long, and tall boulders. Using the same protection as standard bouldering climbers venture up house-sized rocks that test not only their physical skill and strength but mental focus. Highballing, like most of climbing, is open to interpretation. Most climbers say anything above 15 feet is a highball and can range in height up to 35–40 feet where highball bouldering then turns into free soloing.

Highball bouldering may have begun in 1961 when John Gill, without top-rope rehearsal, bouldered a steep face on a 37-foot (11 meter) granite spire called “The Thimble”. Gill’s achievement initiated a wave of climbers making ascents of large boulders. Later, with the introduction and evolution of crash pads, climbers were able to push the limits of highball bouldering ever higher.

7. FREE SOLOING

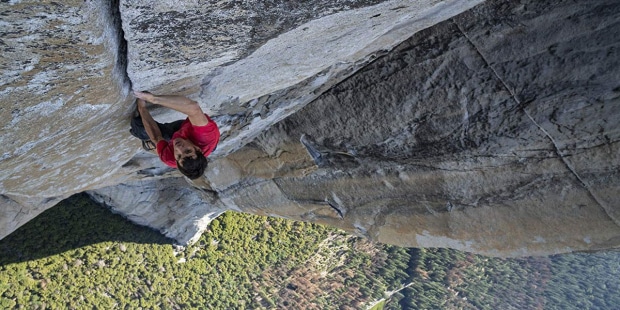

Free solo climbing or free soloing, is a form of technical ice or rock climbing where the climbers (or free soloists) climb alone without ropes, harnesses or other protective equipment, forcing them to rely entirely on their own individual strength and skill. Free soloing is the most dangerous form of climbing, and unlike bouldering, free soloists climb above safe heights where a fall would result in serious injury or death. Commitment, mind control and absolute focus on the climb are needed, because no errors are allowed.

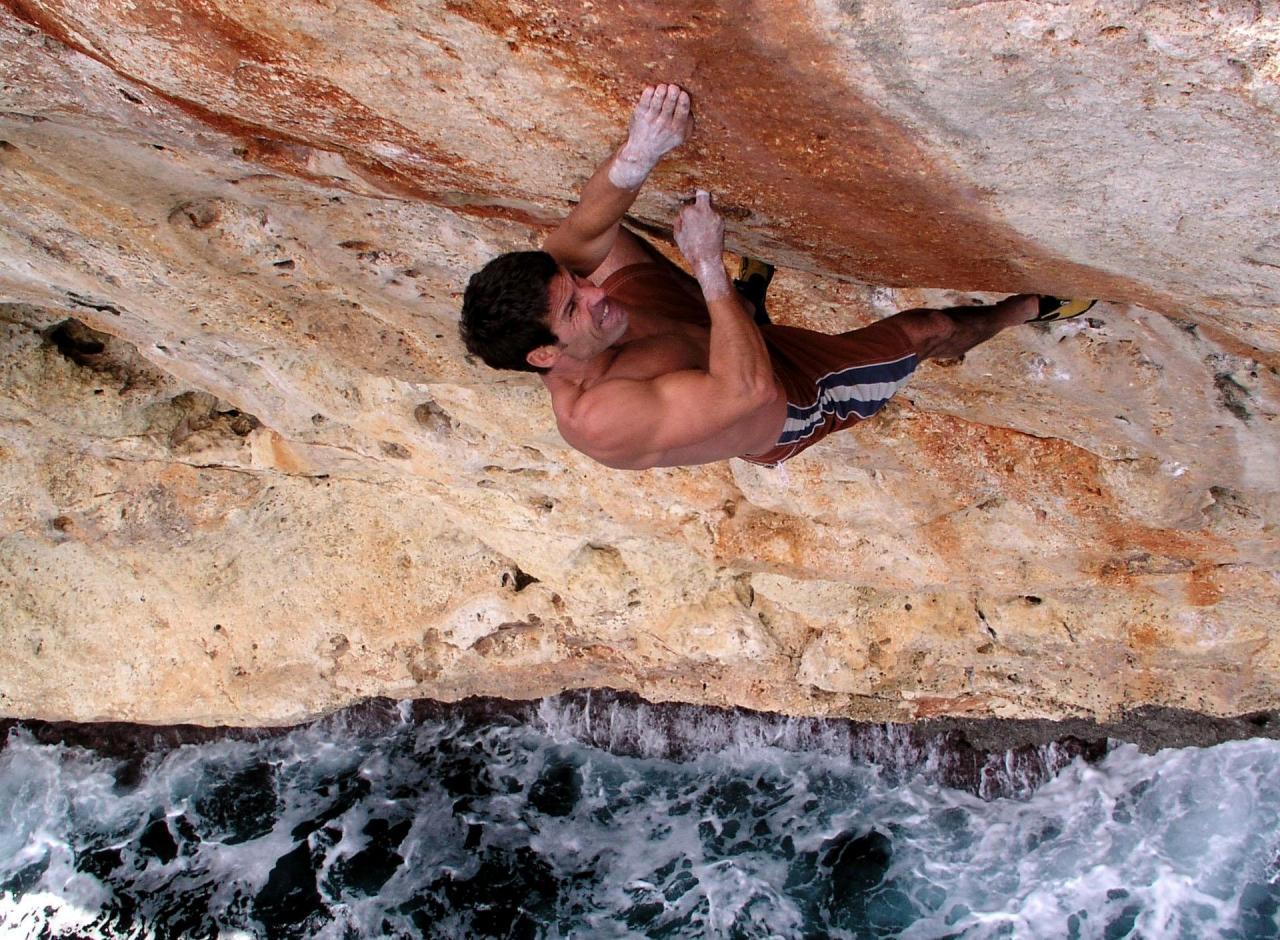

8. DEEP WATER SOLOING

Free climbing an area that overhangs a deep enough body of water to allow for a safe fall. Deep-water soloing (DWS), also known as psicobloc,is a form of solo rock climbing that relies solely upon the presence of water at the base of a climb to protect against injury from falls from the generally high-difficulty routes. While typically practiced on sea cliffs at high tide, it can also be done on climbs above reservoirs, rivers, and even swimming pools. The practice of deep-water soloing in Majorca has its roots in the late 1970s. In 1978, Miquel Riera became frustrated with the aid climbing routes in his local area, so he went to Porto Pi, Palma with his friends Jaume Payeras, Eduardo Moreno and Pau Bover in order to find routes that they could free climb. This became Majorca’s first bouldering venue, and as time went Riera progressed onto the short sea cliffs near there. It was named “Psicobloc”, which, when translated literally into English, means “Psycho Bouldering”

During the 1980s, psicobloc was overshadowed by sport climbing, which was growing greatly in popularity, but this did not stop Riera from continuing his obsession, as he put up many new routes and published articles in the Spanish climbing press.

DWS became more mainstream amongst climbers when a couple of short films were made by popular climbing filmmakers BigUp Productions in 2003. The films featured some of the sport’s pioneers: Tim Emmett, Klem Loskot, and a newcomer to the style, Chris Sharma.

9. INDOOR/GYM CLIMBING

Indoor climbing is an increasingly popular form of rock climbing performed on artificial structures that attempt to mimic the experience of outdoor rock. The first indoor climbing hall in the world was inaugurated in Bolzano, Italy in 1974.

The proliferation of indoor climbing gyms has increased the accessibility, and thus the popularity, of the sport of climbing. Since environmental conditions (ranging from the structural integrity of the climbing surfaces, to equipment wear, to proper use of equipment) can be more controlled in such a setting, indoor climbing is perhaps a safer and more friendly introduction to the sport.

The first indoor walls tended to be made primarily of brick, which limited the steepness of the wall and variety of the hand holds.More recently, indoor climbing terrain is constructed of plywood over a metal frame, with bolted-on plastic hand and footholds, and sometimes spray-coated with texture to simulate a rock face.

Most climbing competitions are held in climbing gyms, making them a part of indoor climbing.

Indoor and outdoor climbing can differ in techniques, style and equipment. Climbing artificial walls, especially indoors, is much safer because anchor points and holds are able to be more firmly fixed, and environmental conditions can be controlled. During indoor climbing, holds are easily visible in contrast with natural walls where finding a good hold or foothold may be a challenge. Climbers on artificial walls are somewhat restricted to the holds prepared by the route setter whereas on natural walls they can use every slope or crack in the surface of the wall. Some typical rock formations can be difficult to emulate on climbing walls.

Always practice Leave No Trace ethics on your climbs, hikes and adventures. Be aware of local regulations and don’t damage natural parks and wilderness.

DREAMPEAKS: ROCK CLIMBING IN MADRID. HIKING IN MADRID. ADVENTURE TOURS AND OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES IN SPAIN.

Text by Gabriel Blanco (Mountain Guide & Climber).